Judith Leyster (1609 - 1660) - Into and out of obscurity

A story of talent, success, erasure, and rediscovery.

Speaking on a panel at the invitiation of the livery company of World Traders, I put Judith Leyster forward as my ‘invisible woman’. This blog is a fuller account of Leyster’s life and legacy, from the perspective of a contemporary woman artist.

Leyster’s story is split into two sections, with a 250 year gap in the middle. The two ends have parallel traits of tenacity, deceipt, prejudice, and dishonourable behaviour.

Rising star

Come with me back to early 17th century Holland, the time of Rembrandt, Franz Hals, and Vermeer. Known as the “Dutch Golden Age”, the economy was thriving*, there was money to spend, patrons with an appetite for ‘genre’ paintings, and a lively culture of artists supplying the market.

Guilds (trade associations, like London’s livery companies) licenced their members to practice their trade, regulating competition and maintaining standards. In cities such as Haarlem (where Leyster was based) the guild for artists and craftsmen was typically called The Guild of Saint Luke.

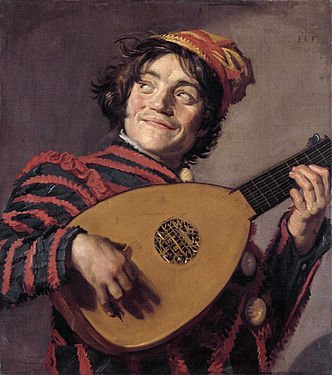

From her late teens, Leyster was getting noticed as a talented artist. It’s not known for sure if she studied with Frans Hals, she at least did a master copy of his ‘Lute Player’ early in her painting journey. Their contemporary David Bailly then did a copy from her copy (look at the hat and fingers to see it wasn’t copied from the Hals). There are various other indications that Leyster and Hals were both competitors and friends. They both produced genre paintings, employing relatively loose brushwork and a similar aesthetic. Personally I find Judith’s brushwork to be more carefully applied, and her subjects to have more depth, less swagger.

Artists applied for membership of city guilds in order to be allowed to operate workshops, take students, and sell paintings.

Self portrait at about 21 - Leyster’s ‘master piece’ submission to the guild

Age 24, Leyster was the first of only 2 woman painters to be admitted as a ‘master’ to the Haarlem Guild Of Saint Luke in the 17th century.

As such, Judith was allowed to legitimately do what she’d been doing anyway, selling paintings! As a guild member she was able to set up a commercial art studio and take apprentices.

Leyster was no pushover, and successfully brought a case regarding one of her students who defected to Hals’ workshop. Hals and the student were fined, as was Leyster for failing to register the student with the guild in the first place. It has been suggested that the kerfuffle of the case caused more positive attention for Leyster’s work… all good publicity!

Fading away

Age 26 she put the kiss of death on her painting career, and legacy, by getting married. Her husband, fellow artist Jan Miense Molenaer was a very productive genre painter. As was customary, Judith proceeded to help run his studio, and gave birth to 5 children (only two survived to adulthood). As far as we know she then painted very little until she died aged 50. It may be that there is more of her mature work out there awaiting discovery. This self portrait was painted in 1653. It doesn’t look like the work of a rusty artist to me. It’s in a private collection, so I couldn’t find a decent resolution photo. To me it speaks volumes of dormant ability, maintained through 5 pregnancies, caring for sick children, and dealing with the tragedy of infant death.

Self portrait age 46

So virtually her entire known output was produced in about 6 years. Imagine what she could have done, given Rembrandt’s 45 active painting years? As a painter I find this inspiring, that such attainment is possible in a short time.

When Leyster’s husband died, her artwork was listed in the post mortem inventory as by "the wife of Molenaer". Thereafter it was largely passed down through family estates, misattributed deliberately or ignorantly to either her husband or Franz Hals.

Roll forward about 250 years, during which time Leyster was completely forgotten. No paintings were attributed to her, they were inherited and dealt as either by Hals or Moelnaer.

Coming out of obscurity

Cornelis Hofstede do Groot

In 1892 - Carousing Couple (now in the Louvre) was sold (as one of Franz Hals’ best works) between London art dealers for £4500. The buyer, Thomas Lawrie realised Leyster’s monogram was under a faked Hals signature, and sued the seller. The case is thought possibly to have been trumped up to create noise around their dealerships (echos of Leyster’s case against Hals?), but anyway it was settled out of court.

Scholar Cornelis Hofstede do Groot (thought to be the one who spotted her distinctive monogram on the painting) recognised it as being on several other paintings he’d seen. Shortly after the case, do Groot published a letter about the misattributions in “The Athenaeum”, under the heading ‘Fine-Art Gossip’. This was the beginning of Leyster’s re-emergence.

Incidentally, it was also do Groot who noticed in 1910 that the Leyster copy of Hals’ Lute player (above), which had been in the Rijksmuseum since 1870, wasn’t actually the Hals that it had been acquired as.

Professor Frima Fox Hofrichter

The sad part is that redress was sought, rather than celebration of the discovery of an unknown Dutch Master. However the celebratory baton has been picked up by Frima Fox Hofrichter and others. I highly recommend her essay (see references below), which reveals the published letter and many more details about the whole sordid affair. A little window into the art world of Victorian London.

In Frima’s 1989 book on Leyster she included another painting “Smiling Boy With Grapes”, having seen it at the LA County Museum of Art in the 1970s. It had come to the museum as by Molenaer. By 1989 they had attributed it to Leyster, and Frima since found Leyster’s monogram on it. But in the 1970s, that it was a painting by Leyster meant nothing, so LACMA sold it, getting $5,750. In 2022 it sold at a Belgian auction for nearly $250k! I have this painting to thank for my valuable correspondence with Frima: I was bothered by the rendering of the boy’s eyes, and saw that it was she who had confirmed the attribution when it was in the possession of the Curren museum. Frima was very welcoming of my enquiry, and generous with her insights. She said that on close observation it was clear Leyster had battled with those eyes.

Boy With Grapes In His Hat - approx 1630

Personally I think this one shows all the signs of being from very early in her career. Anyone who went to the Hals exhibition in the National Gallery recently might have noticed that he too had off days. Should a practicing artist be ruthless with their ‘wiper’s? Or keep them at the back of the plan chest? Or send them out into the world, to someone who likes them? I certainly cringe at some of the work I have kept or sold in the past, and will hopefully improve enough to cringe with hindsight at my current output.

Maestro Michael John Angel

Returning from 3 years abroad in 2017, I wanted to learn how to use oil paints. I went to the National Gallery in London, and pressed my nose up against a lot of paintings. I bought their companion guide (published in 2016) in the gift shop. To my huge dismay, there were only 2 female artists listed in the entire book - Gentileschi and Elizabeth Vigee le Brun. For context, Katy Hessel started her seminal instagram account @thegreatwomenartists in 2015.

Then in 2018 I enrolled on a summer workshop at the Belfast Academy of Realist Art. For two weeks in Belfast, we effectively crammed a full oil painting education, under the brilliant teaching of ‘Maestro’ Michael John Angel. Maestro trained under Annigoni, and runs the Angel Academy in Florence, teaching traditional indirect oil painting techniques, broadly using an atelier system.

The main exercise we did was a master copy, working from large scale high resolution photographs of the original paintings. In the pre-amble correspondence for the course, Maestro offered us a choice of about 5 ‘master paintings’, from which to choose one to copy. With hindsight, considering the state of the art world (as evidenced by the National Gallery collection), I am surprised and grateful that one of the paintings he offered us was Judith Leyster’s Flute Player. The painting is a great demonstration of her talent for genre, portrait and still life painting. Maestro told us Leyster’s story, how underrated and forgotten she was. That to me was a demonstration of allyship before it was fashionable - we learned much more than just technique. Luckily, I recorded a short clip of Maestro dropping pearls of wisdom, and you can see the photo reproductions of the Leyster painting on the table in front of him:

So to close, here is my cringeworthy copy of Leyster’s masterpiece, which represents the beginning of my own appreciation of her skill. I hope you will bear in mind it was one of my very first oil paintings, but I learned a great deal, as you always do when copying masterpieces. Without this exercise I wouldn’t have noticed that he’s wearing the same coat as the Smiling Boy With Grapes (see above), I wouldn’t have noticed the patch on his elbow, or the broken chair.

As a very keen draughter and printmaker, with a passion for working from life, I was desperate to try just one little thing from observation, even though it wasn’t part of the course. So I wrote ‘After Leyster’ on a scrunched piece of paper, and attempted to copy it onto my painting. I don’t think any scholars are needed to refute that my copy was by Leyster’s hand, but just in case, it’s clear! What I didn’t know till later was that Leyster had wittily chosen to put her monogram where the recorder maker would normally put their maker’s mark - at the top of the mouthpiece. I do play the recorder, it’s a wonderful (underrated) instrument, and I’m happy to have retained a dash of her monogram while rendering the mouthpiece.

*The ‘Dutch Golden Age’ was largely funded by affiliation with the East India Company and West India Company - thousands of miles away in the Americas, Southern Africa and Asia, the Dutch colonialists had profitable trading posts and colonies of enslaved people.

References

This blog is a tribute to Leyster, and to those who uncover and share knowledge of historically lost talent.

Wikipedia (ad infinitum!)

https://drrichardstemp.com/2020/04/21/day-34-judith-leyster/

Frima Fox Hofrichter’s essay “A fresh look at an old case The discovery of Judith Leyster” in the publication “Connoisseurship Essays in Honour of Fred G. Meijer”.

Frima’s book “Judith Leyster (1609-1660): A Woman Painter in Holland's Golden Age”

This lecture including the story of the revelation of a hidden figure in a Leyster painting:

Sign up to my newsletter for a free guide on “how to get the best out of an artist”, invitations to events, news, and my blog.

To share this blog, just copy and paste this text: https://www.gailreidartist.com/blog/leyster into messages, Facebook, emails, LinkedIn, X, Y, Z, wherever you like! If you want to tag me on social media that would be great, @gailreidartist across the board. Thank you so much for reading, and for all the lovely messages xxx